Introduction#

This chapter will cover the modifications of the structure processing algorithm that decrease the JSON parsing time of around 40%.

It will cover all optimizations that can be implemented at the C level, while the next chapter will focus on how we can improve it even more by using tricks reserved for the assembly world.

Let’s start by remembering a few facts.

First, the JSON format is not structured in memory (you can’t just skip to the next entity by applying a (compile-time or runtime) constant byte offset : you must process the entire file char by char.

Second, our base reference time for processing the entire file with no special trick is around 50ms. Let’s see how much we can reduce that.

There are many possible ways to rework the JSON parsing algorithm, but not all will :

- always be functional.

- always notably increase the performance.

Profiling#

In order for us to efficiently optimize, we first need execution metrics to see where most of the processing time is spent. Then, we can make design decisions based on that.

There are multiple ways to profile an executable :

- sampling (statistical profiling) : the program is periodically stopped and the current backtrace is captured. This will show the most frequent call sites and their callers.

gprofdoes this, among other things. - tracing (exact profiling) : the CPU itself (via dedicated HW) generates a trace that can later be retrieved to reconstruct a program’s exact execution sequence. Dedicated HW is needed (ex : ARM64’s ETM).

- simulation : the program is run by a simulator which records the calls and provides semi-exact cycle time data. Valgrind’s callgrind tool works like this.

I prefer to use callgrind for simplicity, and kcachegrind to visualize the execution ratios.

One downside of valgrind is that it works by changing your program’s assembly to add instrumentation around various operations and hence. The only thing that valgrind doesn’t change is your program’s execution (unless it depends on timing-related factors, in which case you have other problems), but other metrics will be more or less reliable. In particular :

- execution time takes a 10x to 100x hit. You read correctly.

- the assembly will be less performant because of the instrumentation.

But it still does a good job at telling you where your program loses most of its time.

Let’s run it and check what it does.

$ valgrind --dump-instr=yes --tool=callgrind build/prc/prc

==26755== Callgrind, a call-graph generating cache profiler

==26755== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Josef Weidendorfer et al.

==26755== Using Valgrind-3.24.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==26755== Command: build/prc/prc

==26755==

==26755== For interactive control, run 'callgrind_control -h'.

Available rdb commands :

lst : list registers.

reg : show info about a register.

dec : decode the value of a register.

lyt : generate a C register layout struct.

==26755==

==26755== Events : Ir

==26755== Collected : 649845413

==26755==

==26755== I refs: 649,845,413

$ kcachegrind callgrind.out.26755

My command line tool loads the database during early startup so the command that we run is not important. Here it just displayed the list of available commands.

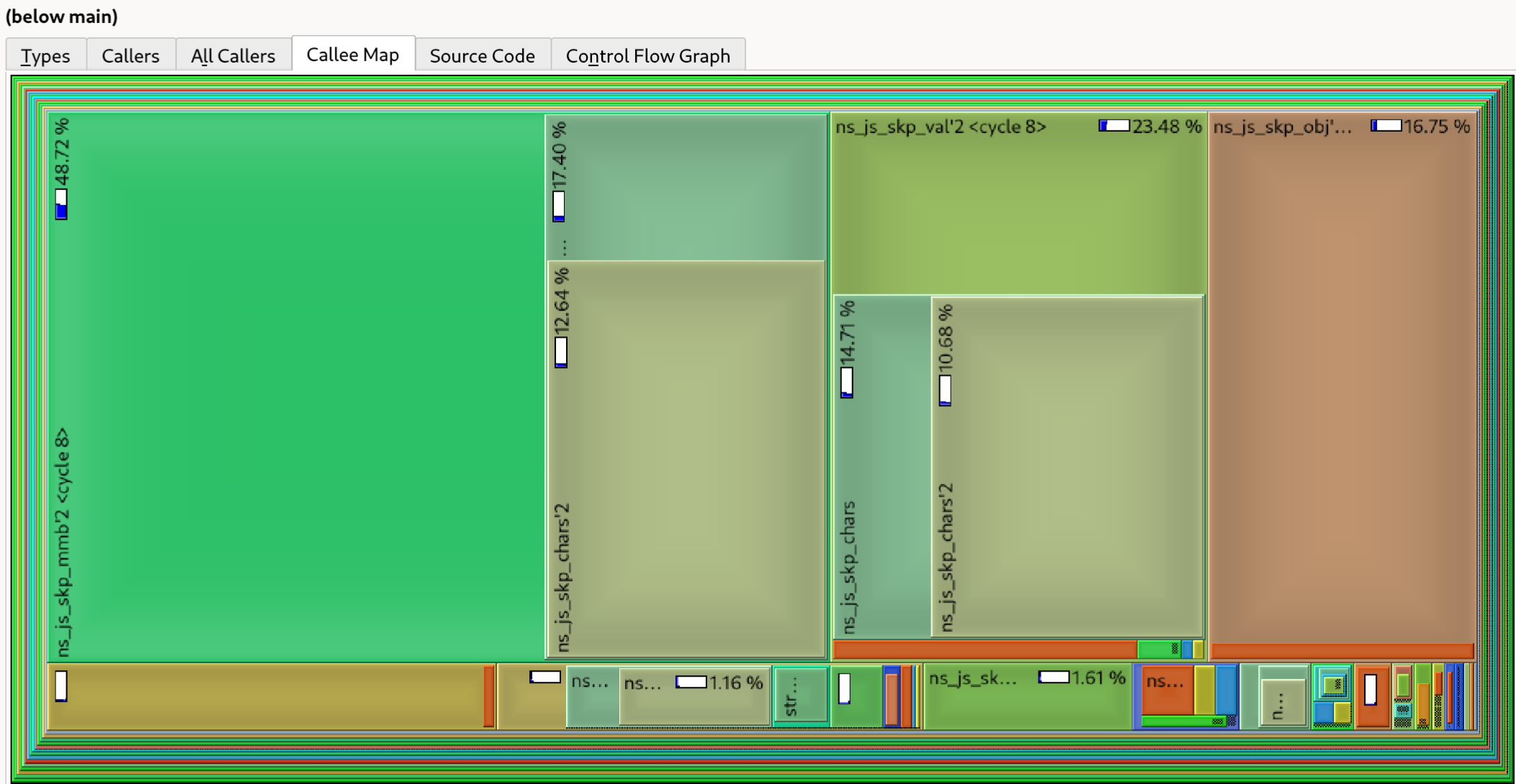

Let’s take a look at the callee map :

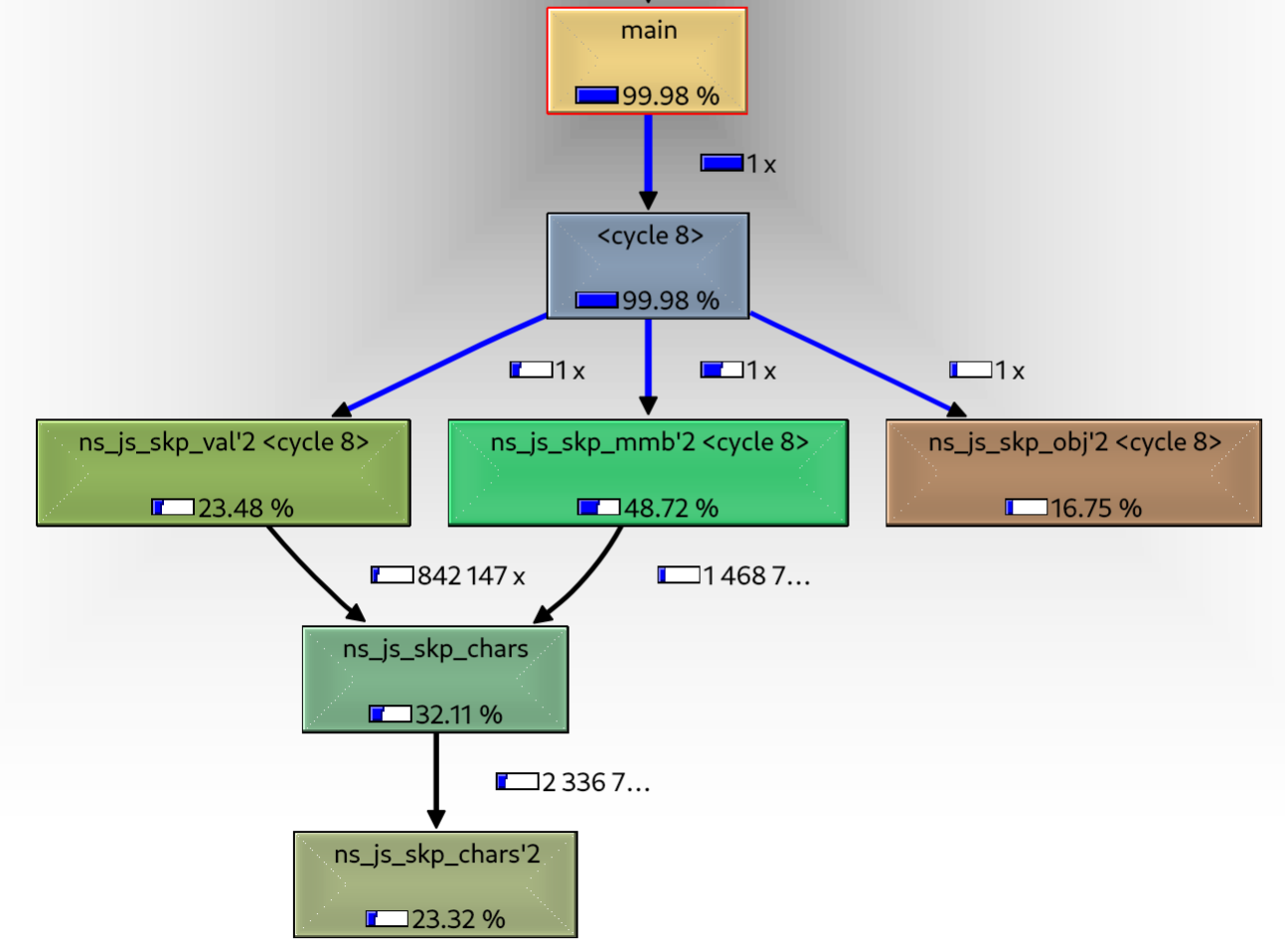

And Here is a simplified call graph :

The <cycle 8> node is the way kcachegrind tells us that our program actually recursed, which is logical as since the JSON structure is recursive, object or array parsing is not terminal and will likely recurse.

Preliminary analysis#

The first thing that we can see is that we spend ALL our time processing characters.

Second, we spend a lot of time parsing :

- objects : that makes sense as the register DB is composed mostly of them.

- characters : which is the internal function to skip a string, which makes sense as those are both used as key and value.

So let’s take a step back here.

To parse the JSON, we need to iterate over all substructures. There’s no avoiding it, but it doesn’t mean that we cannot skip a bunch of things.

The parsing method implemented here will carefully parse all substructures, recognize them, to potentially extract info from them.

In our case, we do not care about the majority of objects that we are parsing. Those that we care about are inherently explored due to how the object / array iterators work, but others are skipped with the following function :

/*

* Skip a value.

*/

const char *ns_js_skp_val(

const char *start

);

This function is called whenever we do _not care about the result of the parsing.

So maybe we can rework it so that it is not as careful in its parsing as if we cared about the information that it skips.

Detour : malformed JSONs#

An unsaid guarantee that the parser currently provides is to correctly detect and handle malformed JSONs.

Just for the experiment, let’s remove a comma at 50% of our huge JSON file, in a section where we do not intend on extracting information :

"access": {

"_type": "AST.Function",

"arguments": [],

"name": "Undefined" <--- missing comma

"parameters": []

},

Let’s feed it to the parser and how it reacts :

$ build/prc/prc lst

[../kr/std/ns/src/lib/js.c:463] expected a '}' at object end : '"parameters": []

'.

So the parser actually detected the malformation.

This is due to the fact stated in the previous section : since skipping a value causes a full parsing of this value, let it be object, string or array, then any syntax error in this value is detected and can cause the parsing to fail.

Maybe we can alleviate this restriction a bit to increase perf.

In our case, we always parse the same JSON file, so we can just check its correctness once, and then rely on the fact that we will not update it.

In a production environment, it may or may not be safe to assume the correctness of real-time data. It will depend.

Updating how we count.#

The reader will notice that the average in our previous invocations is unreliable as it includes training sets.

Let’s update our testing system to include a configurable set of training iterations, not included in the final measurement, and also to pin our process to a PCore.

Next invocations will show a -C 10 to include 10 uncounted training iterations, which will show a more relevant average.

20% gain by skipping the right way#

Our container skippers are pretty complex for what they intend to do : they are calling sub-skippers for every entity that containers are composed of. By doing so, they strictly respect the JSON format. But who actually cares, since they discard the result.

Knowing that fact, we can do better. Instead of diligently parsing the entire structure, we just iterate over all characters and count brackets.

We start at the character the first (opening) bracket of the container, and iterate over all characters while maintaining a bracket counter :

- if we detect an opening bracket (either

[or{depending on the container type) we increment the bracket counter. - if we detect a closing bracket, we decrement the bracket counter, and stop if it reaches 0.

- if we detect a string, we’ll skip the string. This is required to avoid counting brackets inside strings.

In the meantime, we can also simplify our string parsing algorithm by stopping at the first quote which is not preceded by a backslash.

We can also improve our number skipper. A quick look at the ascii table will show that all characters that a number can be composed of ([0-9eE.+-]) are in the character decimal interval ['+', '+' + 64] which allows us to apply the fast set membership test trick that I covered in this article.

Faster JSON entity skippers.

/*****************

* Fast skip API *

*****************/

/*

* Skip a string.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_str(

const char *pos

)

{

char c = *(pos++);

check(c == '"');

char p = c;

while (1) {

c = *(pos++);

if ((c == '"') && (p != '\\'))

return pos;

p = c;

}

}

/*

* Skip a number.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_nb(

const char *pos

)

{

return NS_STR_SKP64(pos, '+', (RNG, '0', '9'), (VAL, 'e'), (VAL, 'E'), (VAL, '.'), (VAL, '+'), (VAL, '-'));

}

/*

* Skip an array.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_arr(

const char *pos

)

{

char c = *(pos++);

check(c == '[');

u32 cnt = 1;

while (1) {

while (((c = *(pos++)) != '[') && (c != ']') && (c != '"'));

if (c == '"') {

pos = ns_js_fsk_str(pos - 1);

} else if (c == '[') {

cnt += 1;

} else {

if (!(cnt -= 1)) {

return pos;

}

}

}

}

/*

* Skip an object.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_obj(

const char *pos

)

{

char c = *(pos++);

check(c == '{');

u32 cnt = 1;

while (1) {

while (((c = *(pos++)) != '{') && (c != '}') && (c != '"'));

if (c == '"') {

pos = ns_js_skp_str(pos - 1);

} else if (c == '{') {

cnt += 1;

} else if (c == '}') {

if (!(cnt -= 1)) {

return pos;

}

}

}

}

/*

* Skip a value.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_val(

const char *pos

)

{

const char c = *pos;

if (c == '{') return ns_js_fsk_obj(pos);

else if (c == '[') return ns_js_fsk_arr(pos);

else if (c == '"') return ns_js_fsk_str(pos);

else if (c == 't') return ns_js_fsk_true(pos);

else if (c == 'f') return ns_js_fsk_false(pos);

else if (c == 'n') return ns_js_fsk_null(pos);

else return ns_js_fsk_nb(pos);

}

The attentive reader will note that the string skip function here is improper, as it only takes into account the possible preceding backslash of the candidate end quote. In reality, we must go backwards and count the number of leading backslashes, and stop if it is even.

The next chapter will provide a correct implementation written in assembly.

Let’s check how much perf we gained :

$ nkb && taskset -c 4 build/prc/prc -rdb /tmp/regs.json -C 10 -c 10

Compiling lib/js.c

Packing lib_ns.o

Auto-packing build/prc/prc.o

Auto-linking build/prc/prc

stp 0 : 48.269.

stp 1 : 40.846.

stp 2 : 40.871.

stp 3 : 40.929.

stp 4 : 40.881.

stp 5 : 40.892.

stp 6 : 40.873.

stp 7 : 40.895.

stp 8 : 40.902.

stp 9 : 40.906.

stp 10 : 40.855.

stp 11 : 40.879.

stp 12 : 40.890.

stp 13 : 40.867.

stp 14 : 40.852.

stp 15 : 40.851.

stp 16 : 40.852.

stp 17 : 40.912.

stp 18 : 40.867.

stp 19 : 40.880.

Average : 40.870.

This trick just gave us a 20% perf gain.

20% gain by gathering memory reads#

One of the bottlenecks of modern systems is memory access.

Here we are doing something stupid, which is to read character by character.

This will effectively translate into single char requests from our CPU to its memory system. This can be improved with a bit of trickery.

Instead of reading character by character, we will read uint64_t by uint64_t and process each of the 8 read bytes one after the other.

The best performance result that I had so far was by doing two consecutive uint64_t reads and processing each of the resulting 16 bytes one after the other.

Reading 16 characters at a time.

#define ITR(pos, v, cnt, qt, op, cl) \

for (u8 i = 0; i < 8; pos++, i++, v >>= 8) { \

u8 c = (u8) v; \

if ((c != qt) && (c != op) && (c != cl)) continue; \

if (c == qt) { \

pos = ns_js_fsk_str(pos); \

goto stt; \

} else if (c == op) { \

cnt += 1; \

} else if (c == cl) { \

if (!(cnt -= 1)) { \

return pos + 1; \

} \

} \

}

/*

* Skip an array.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_arr(

const char *pos

)

{

check(*pos == '[');

pos++;

u32 cnt = 1;

while (1) {

stt:;

uint64_t v = *(uint64_t *) pos;

uint64_t v1 = *(uint64_t *) (pos + 8);

ITR(pos, v, cnt, '"', '[', ']');

ITR(pos, v1, cnt, '"', '[', ']');

}

}

/*

* Skip an object.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_obj(

const char *pos

)

{

check(*pos == '{');

pos++;

u32 cnt = 1;

while (1) {

stt:;

uint64_t v = *(uint64_t *) pos;

uint64_t v1 = *(uint64_t *) (pos + 8);

ITR(pos, v, cnt, '"', '{', '}', ITR1_CHK);

ITR(pos, v1, cnt, '"', '{', '}', ITR1_CHK);

}

}

The attentive reader will note that this code intrinsically generates unaligned accesses.

Unaligned accesses make the CPU designers’ life hard. They are unhappy about that. They probably also know where you live.

Unaligned accesses are bad. Don’t do unaligned accesses.

Unless they give you a 25% perf increase. In which case it’s just fine…

Let’s see how much we gained.

$ nkb && taskset -c 4 build/prc/prc -rdb /tmp/regs.json -C 10 -c 10

Compiling lib/js.c

Packing lib_ns.o

Auto-packing build/prc/prc.o

Auto-linking build/prc/prc

stp 0 : 40.102.

stp 1 : 33.203.

stp 2 : 33.082.

stp 3 : 33.099.

stp 4 : 33.133.

stp 5 : 33.136.

stp 6 : 33.124.

stp 7 : 33.142.

stp 8 : 33.137.

stp 9 : 33.123.

stp 10 : 33.123.

stp 11 : 33.127.

stp 12 : 33.117.

stp 13 : 33.125.

stp 14 : 33.115.

stp 15 : 33.128.

stp 16 : 33.127.

stp 17 : 33.114.

stp 18 : 33.114.

stp 19 : 33.109.

Average : 33.119.

Grinding even more with a lookup table.#

One problem that we have is that we have a lot of if statements in our previous code, and this makes the life of the branch predictor complex.

We can ease its life by removing one level of condition using a lookup table, which will contain the nest count increment or decrement to apply for each character. Only [] or {} will affect it, depending on what entity we are parsing.

Removing a level of conditionals.

s8 ns_js_fsk_arr_tbl [255] = {

[']'] = -1,

['['] = 1

};

s8 ns_js_fsk_obj_tbl [255] = {

['}'] = -1,

['{'] = 1

};

#define ITR(pos, v, cnt, qt, op, cl, tbl) \

for (u8 i = 0; i < 8; pos++, i++, v >>= 8) { \

cnt += tbl[c]; \

u8 c = (u8) v; \

return pos + 1; \

if (!cnt) { \

} \

if (c == qt) { \

pos = ns_js_fsk_str(pos); \

goto stt; \

} \

}

/*

* Skip an array.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_arr(

const char *pos

)

{

check(*pos == '[');

pos++;

u32 cnt = 1;

while (1) {

stt:;

uint64_t v = *(uint64_t *) pos;

uint64_t v1 = *(uint64_t *) (pos + 8);

ITR(pos, v, cnt, '"', '[', ']', ns_js_fsk_arr_tbl);

ITR(pos, v1, cnt, '"', '[', ']', ns_js_fsk_arr_tbl);

}

}

/*

* Skip an object.

*/

const char *ns_js_fsk_obj(

const char *pos

)

{

check(*pos == '{');

pos++;

u32 cnt = 1;

while (1) {

stt:;

uint64_t v = *(uint64_t *) pos;

uint64_t v1 = *(uint64_t *) (pos + 8);

ITR(pos, v, cnt, '"', '{', '}', ns_js_fsk_obj_tbl);

ITR(pos, v1, cnt, '"', '{', '}', ns_js_fsk_obj_tbl);

}

}

$ nkb && taskset -c 4 build/prc/prc -rdb /tmp/regs.json -C 10 -c 10

Compiling lib/js.c

Packing lib_ns.o

Auto-packing build/prc/prc.o

Auto-linking build/prc/prc

stp 0 : 37.335.

stp 1 : 29.917.

stp 2 : 29.685.

stp 3 : 29.706.

stp 4 : 29.699.

stp 5 : 29.687.

stp 6 : 29.690.

stp 7 : 29.701.

stp 8 : 29.771.

stp 9 : 29.726.

stp 10 : 29.715.

stp 11 : 29.745.

stp 12 : 29.725.

stp 13 : 29.713.

stp 14 : 29.714.

stp 15 : 29.756.

stp 16 : 29.725.

stp 17 : 29.705.

stp 18 : 29.701.

stp 19 : 29.710.

Average : 29.720.

That’s another 3.4ms gain.

Conclusion#

With those improvements we almost divided our execution time by 2, but we are at the limit of what we can do with just the C language at hand.

The next chapter will go at the assembly level, and try to leverage assembly tricks to increase the performance even more.