The previous chapter of this series presented the different software components that constitute our trading, and provided some of the reasons for their existence.

As we saw in this chapter, the central part of this trading system is the trading core, which runs our strategies, either in real time for actual trading, or in simulation for backtesting.

The full picture#

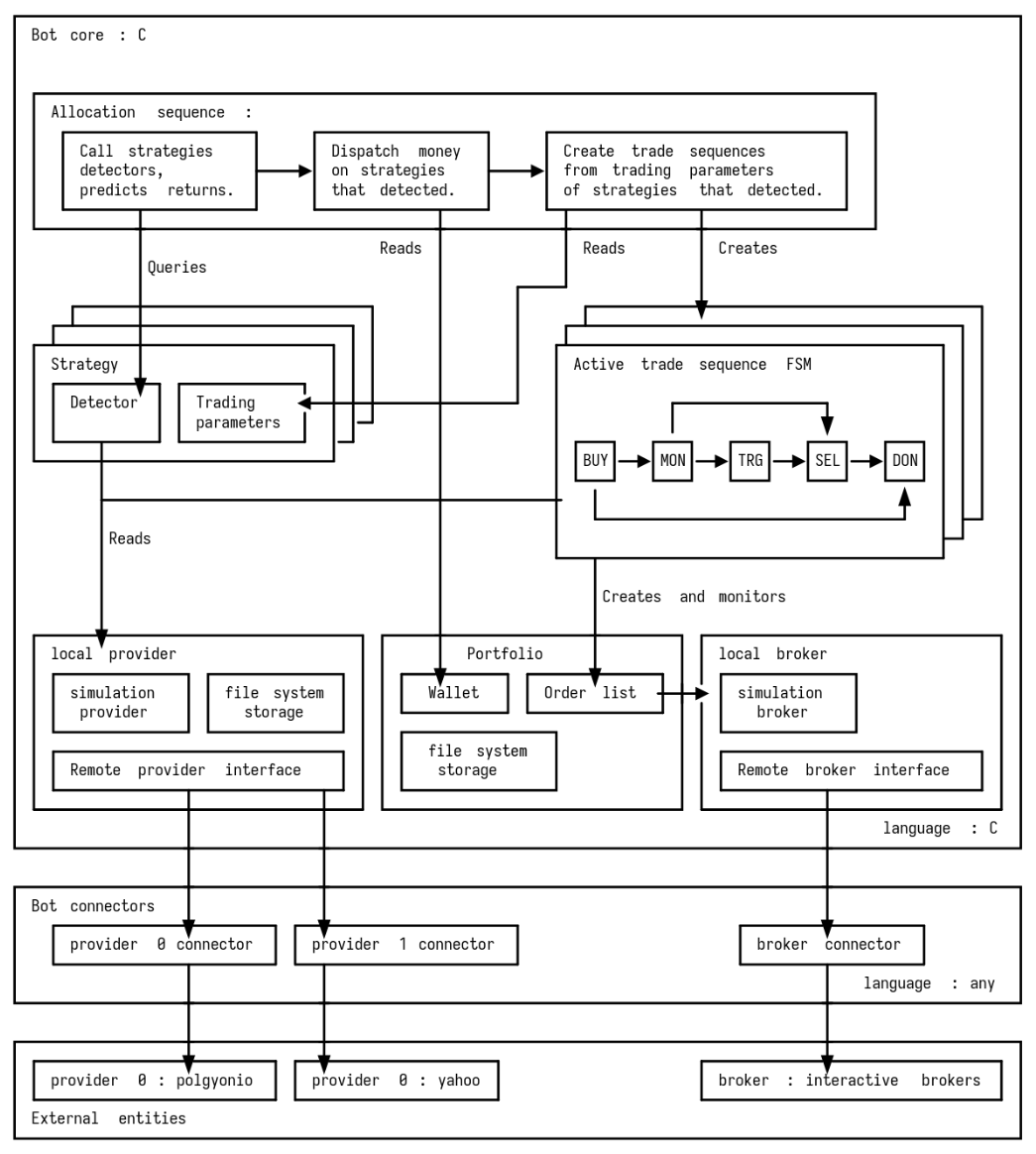

For the record and to illustrate before diving in, here is a full diagram of the trading core, presenting its components and the entities it interacts with.

At first glance, we can identify three main groups :

- core components : the components of the trading core, which are all part of the same executable. Hence, they are all programmed in pure C and are ideally self-contained, in the sense that they do not incorporate third party code.

- remote providers and remote brokers : the services that provide data used as a strategic decision base, and that receive and process actual trading orders. The protocol that they use to communicate depends on the company that provides those services, and we cannot expect much standardization.

- connector components : those components bridge the gap between the trading core which is simple and self-contained by design, and the complex protocols that either remote provider or remote brokers require to communicate. They likely use libraries provided by the providers or brokers, and hence, we cannot infer anything in the language that they use. We only need to standardize the way they communicate with the trading core. In practice, connector components are running in their own processes, and communicate with the trading core via either unix sockets or named pipes, using a simple packet-based protocol.

In reality, since most data providers support rest-ful APIs, the trading core executable uses libcurl in the provider interface to avoid the need of a provider connector for performance reasons. The broker connector will likely be present though, as interacting with remote brokers is complex and is usually done via libraries provided by the brokers themselves. Also in this case, performance does not really matter.

Let’s now take a look at the fundamental concepts behind this rather convoluted design.

Strategies#

Based on what we established in the previous chapter, we want the strategies ran by the core to be :

- dynamic : we need the trading core to be regularly updated to reflect the most recent findings of the miner.

- backtestable : the miner needs to simulate the past behavior of a given candidate strategy to deduce its past return on investment, as a hint for its future return on investment.

Internally, a strategy is characterized by three things :

- a target instrument that it buys or sells.

- a currency, in which this instrument is traded.

- a detector, which reads historical data from the past and present and detects certain conditions (ex : an increase of more than X% in a given stock price). Upon detection, it makes a prediction on the future return on investment that buying the target instrument now would generate.

- trading parameters, which upon detection, describe the process of buying the target instrument, monitoring its price evolution, and deciding when it should be sold.

Detectors can vary a lot and characterize the implemented strategy.

Trading parameters describe in which modalities the trading core buys and sells.

Trade sequences are very similar across different strategies : they invest a certain amount of money in the target instrument, and wait for certain conditions to be met to sell the previously bought instrument.

Hence, and since buying and selling is a rather critical part of the trading core, it is accomplished by a dedicated library, the trade sequence lib, which will be described in a dedicated chapter.

Assets and portfolio#

The trading core manipulates different assets, and passes orders, entities that are tracked by a library called the portfolio.

The first one and most obvious asset is money, which comes in different currencies. The wallet (sub-lib of the portfolio) tracks every money depot available to the trading core.

The second type of asset is instruments, like stocks, options, which can be traded.

One could argue that currencies can also be traded, a totally acceptable nuance, that I’ll happily ignore as my implementation is not targeting currency trading. But that would be a valid point and I have not given enough thought on how/if it would change the portfolio design.

In practice, it is likely that the broker offers us ways to query our trading account’s assets list. Although, I made the choice of not relying on the broker’s info, as I wanted to support multiple bots using the same brokerage account. In this case, there would be no way for bots A and B to know which assets of the brokerage account are allocated to each other.

Consistency, fault tolerance, and on-disk portfolio storage#

Since the previous section argued in favor of each bot having its own portfolio and asset management, managing this per-bot portfolio must be done very carefully. If there is any accounting error, the bot may end up spending more money that was originally assigned to it, or sell more stocks that it bought, possibly eating on stocks of the brokerage account that are owned by other bots using the same brokerage account.

I made the choice of relying heavily on file system import and export to save the state of the portfolio, while also ensuring fault tolerance.

Since order passing (whose intricacies with the portfolio are described below) is relatively rare in a system with a response period of one minute, it is acceptable to completely export the portfolio to disc before and after updating (passing, completing, cancelling) any order. This way (and with the careful export of the remaining trading core components at the same time), if the trading core faults for some reason, the previously exported (and valid) state of the portfolio can be used when restarting the trading core, and the asset accounting system is not in danger.

Order passing, and assets usage#

One of the fundamental goals of the trading core is to pass (profitable) orders to the broker.

The order passing logic must respect the limits of the portfolio, understand : we must not invest more money than we have, and we must not sell more instruments than we own.

A simple strategy (which makes accounting a bit harder for a portfolio with pending orders) is to just un-count any asset used to pass an order from the portfolio. Then, two things can happen :

- if the order is cancelled (either by the bot but ultimately by the broker which confirms the cancellation) then assets are re-added to the portfolio.

- if the order is (partially or fully) executed, then some assets are consumed (money in case of buying a stock), some are re-added to the portfolio (part of the money if not all of it was invested) and some new assets are added (the bought stocks).

A consequence of this is that order descriptors (what we want to buy/sell, how much of it we want to buy/sell, for what price, how much we ended up buying/selling) must be very accurately tracked by the trading core, in collaboration with the broker : when an order is complete, we need to query the broker so that the portfolio has all the info it needs to maintain its bookkeeping.

Otherwise, the portfolio would inaccurately track its assets which could lead to the catastrophic scenarios mentioned before :

- a bot using more money than what it was authorized to handle, which is troublesome if multiple bots use the same underlying trading account.

- a bot selling more stocks than what it bought, which is also a problem in the scenario above.

Allocation#

The allocation algorithm is the heartbeat of the trading core.

It consists on a routine called periodically, which does three things :

- first, it calls the detector of each strategy, which returns :

- 0 if we should not trade now for this strategy.

- a non-zero weight if the bot should trade following the strategy’s trade parameters. This weight will be used right after to decide how much money is allocated to the trade.

- then, for each currency listed in the portfolio :

- it calculates the sum of weights of all strategies whose :

- detector returned a non-zero weight; and

- target instruments trade in this currency.

- then for each of these strategies, it allocates M = C * w / W money to this strategy, with :

- C : the total amount of this currency that can be traded.

- w : the weight returned by the strategy’s predictor.

- W : the total weight calculated previously.

- it calculates the sum of weights of all strategies whose :

- then for each strategy that it allocated money to, it creates a trade sequence using :

- the allocated amount.

- the strategy’s trade parameters.

As stated before, trade sequences are not implemented by strategies themselves. They use a generic algorithm, and strategies only provide their own configurations for the generic trade sequence. Their involvement in the trading core hence stops here.

General considerations on the provider#

This section will not describe the provider in a technical manner, as this will be done in a dedicated chapter.

Rather, it will first define the entities involved in the provision and consumption of historical data, and introduce the problems that the provider design has to solve.

Let’s first define the terms :

- remote provider : the entity that provides the historical data (ex : polygonio).

- provider, or local provider : the block of the trading core that :

- queries the remote providers for historical data.

- stores the downloaded data locally on disk.

- reads this data from disk when decisions need to be made based on it.

Remote providers like polygonio offer different prices for different historical ranges :

- if you pay the low price, they only allow you to access historical data between (now - 15 minutes) and (now - 3 years). If you want real time data, you have to pay a much higher price.

- other providers (like your actual broker) may give you access to the most recent data but may not go as far in the past

It is thus important to support multiple remote providers. When the local provider needs to download data in a time range, it selects a source that can provide this time range and downloads the data from it.

The backtesting capability of the trading core affects the design of the local provider. Indeed, in order to take advantage of the full processing power of our processor, the miner will start multiple backtesting sessions in parallel, each running in a dedicated process, for each strategy candidate. These backtesting sessions will likely test variants of the same high level strategies for the same target instruments, and hence, will use the same historical data.

Each one of these processes will have its own local provider, and the question is then : does each local provider have its own storage ? Formulated differently : can multiple instances of the local provider share the same disk storage, or do they have to re-download the data from the remote providers ?

As the reader can guess, mandating each backtesting session to re-download everything would be dramatic for perf. To give you numbers :

- Backtesting a single strategy involving AAPL and NVDA over a 3 month period takes roughly 3 seconds.

- Downloading this amount of data from polgonio takes roughly 15 seconds, or 5 times more. Hence, we must reduce unnecessary downloads as much as possible.

Thus, having each local provider have its own storage and re-download data from the remote provider just doesn’t fly. We need multiple local providers to share the same storage efficiently.

Hence, we must design the local provider in a semi-clever way so that :

- multiple local provider instances can be spawned;

- they share the same disk storage.

- they collaborate on the update of this disk storage.

- they do this as efficiently as possible.

The actual implementation of the local provider is surprisingly simple in terms of number of lines, but has a high conceptual/nb_of_lines ratio. Many design choices do impact the overall perf, and this, the local provider implementation will be covered in a dedicated article.

Local broker, remote broker, simulation broker#

We will use the words local and remote to qualify brokers the same way we did to qualify providers.

A remote broker is the entity that our trading core must reach out to to pass orders.

The local broker is the part of the trading core that allows strategies to :

- passing new orders.

- getting the status of our orders in flight.

- cancelling orders.

There are two types of local brokers.

The live broker is the local broker that is used for active trading : it forwards the order management requests to a remote broker (ie : crafting requests to and reading responses from the remote broker’s servers, possibly using a library provided by the said broker). Note that because of what we covered in the section dedicated to the portfolio, the broker does not get the portfolio’s composition from the remote broker.

The simulation broker is the local broker that is used for backtesting. Its goal is to simulate the execution of the order passing requests, using historical data. It uses the local data provider to query the price of an instrument target of an order at the (past) order passing time and reports the order complete at that price (or acts in a more evolved way based on the stop and limit prices of the order).

It inherently assumes that the orders that are passed by the trading core have no effect on the effective prices, which as of last time I checked my bank account, sounds like a reasonable assumption for a bot using it.

Backtesting#

As a reminder, the trading core has two operation modes :

- real-time where real orders are passed.

- simulation where we want to compute the return of a set of strategies.

For both testing and correctness, it is important to have the backtesting algorithm behave as close to the real time trading algorithm as possible.

Ideally, we want to have the exact same code running in both cases, which is possible, with the only exception being the broker, as we cannot ask interactive brokers to pass orders in the past. We will need a dedicated component, the simulation broker, described in the broker section below, which will pass orders based on the provider’s historical data.

All other elements of the trading core can behave the same way.

Hence, in practice, backtesting only removes the need for a remote broker, which simplifies the structure of the trading core.

Here is the diagram representing the components the trading core used when backtesting.