Introduction#

In the previous chapter we defined the base characteristics of the system managed by a memory manager. Additionally, we also defined the primary memory manager as the sub-system of the memory manager responsible for :

- referencing primary memory blocks.

- allocating page blocks in these primary memory blocks.

The primary memory manager’s allocation system is required to :

- be stand alone and not depend on any external allocator to store it’s allocation metadata.

- support both allocation and free.

- avoid internal fragmentation, i.e. allocate more memory than needed.

- avoid external fragmentation, i.e. coalesce contiguous free regions when possible.

This chapter aims to complexify and provide a more detailed look at the system the primary manager has to work in by introducing the concept of memory zone, as well as developing the previously introduced concept of memory node.

Then, we will present the base algorithm for managing the primary memory for a single zone of a single node.

Finally, we will conclude by a detailed diagram summarising the memory manager’s architecture.

DMA and the need for memory zones#

In the first chapter we described physical memory as an uniform resource with no other differentiating characteristics apart from it the NUMA node dimension. This was an oversimplification, and in order to better explain how things really work we need to introduce the concept of Direct Memory Access.

Some peripherals like UART may rely exclusively on memory-mapped registers to receive or send data to and from the operating system. In these cases, they may have a small internal buffer accessible through these memory mapped registers, that the OS must periodically read/write to.

This read/write sequence is often executed in an interrupt sequence, triggered by the device when it has transmitted or received data.

Though this sequence may be suitable for embedded systems where the relative temporal cost of an interrupt is not that high (note to the reader : I am not saying the cost is low), with low bandwidth devices that do not force the OS to permanently poll the device, it clearly shows its limits in modern systems where the cost of an interrupt is non-neglectable, or with devices with a higher bandwidth.

To solve this issue, communication peripherals now present Direct Memory Access (DMA) capabilities that give them the means to directly read/write the data they receive/send to memory.

Their memory operations are done in physical address space, they directly (or indirectly in the presence of an IOMMU, which we will not go into as this is out of the scope of our topic) access the physical address space.

The Operating System has to allocate primary memory buffers that these devices can use, and notify them that they must read/write to those buffers.

The device now has the liberty to schedule its reads/writes depending on its own constraints, and will only wake up the OS when it needs new buffers.

But this raises an issue though : the physical address space may be a 64 bits address space, and some devices may not support it : their accessible addresses will be 16 or 32 bits long. The OS nowhas to ensure that primary memory allocated for peripheral DMA is effectively in the target periperal’s accessible address range.

For this reason (there are other use cases, for example Linux’s HIGHMEM zone), the concept of memory zone emerged. It simply consists of considering not one homogeneous set of primary memory blocks, but rather considering multiple sets, or zones, each one containing memory suited for one type of usage.

Linux systems generally exhibit the following zones :

- DMA16 : primary memory with 16 bits addresses.

- DMA32 : primary memory with 32 bits addresses.

- NORMAL : primary memory used by regular software.

- HIGHMEM : primary memory that cannot be permanently mapped in kernel space.

Each zone will have its own primary memory allocator.

Additional details :

Exploring the HIGHMEM concept : ndocumentation

NUMA and the need for a memory manager per node#

As defined in the previous chapter, a node is a conceptual set containing memory banks and cores. The respective nodes of a core and a memory bank are the only information the OS uses to determine the latency of the access from a core to the memory bank.

This latency information is fundamental for the primary memory manager, as its role is to provide memory to all different cores. Its objective will be to provide to each core primary memory that will be optimized for the smallest access latency. All whilst respecting external constraints such as the zone the primary memory must be part of.

To achieve this, the memory manager must be decentralised, and each node will have its own memory manager.

This node memory manager will have a set of zones, and each zone will have it’s own primary memory allocator. Each core will know the node it belongs to, and so, will query the related node’s manager for allocation / deallocation of primary memory. The node manager will then transfer the request to the primary memory allocator of the related zone.

More details on NUMA :

- What is NUMA | The Linux Kernel documentation

- Non-uniform memory access | Wikipedia

- Understanding NUMA Architecture

NUMA Fallback#

The procedure described in the previous paragraph raises the question : what if the selected zone allocator runs out of memory ?

One of the constraints of the NUMA system that we have described was that each core in the system could access each memory bank. Only the access latency varies.

Following this constraint, all the allocator has to do is to select a compatible fallback zone allocator and forward the allocation request to it.

This fallback zone could be determined at allocation time, but, as the constraints that would help guide this choice are entirely known at compile-time, this might not result in the most optimized solution. As you might already have guessed, these constraints are :

- memory latency, purely node-dependent.

- zone compatibility, known by design : DMA16 should be compatible with DMA32, DMA32 with NORMAL etc…

As a consequence, it is possible to define this zone that the fallback allocator should use both at startup or compile-time.

Linux, for example, keeps for each zone of each node a constant array of fallback zones references, that can be used when the zone’s allocator runs out of memory.

Problems really arise when all of these fallback zones also run out of memory. We are left in a bind as the memory manager cannot invent memory : if all of our allocators end up starving, the system should crash, at least in a controlled way.

Additional details ( if you dare ):

- mmzone.h - include/linux/mmzone.h - Linux source code (v5.14.6) | Bootlin

- mm_types.h - include/linux/mm_types.h - Linux source code (v4.6) | Bootlin

Primary memory dispatch#

When the system boots, primary memory blocks positions and sizes are either :

- Read in a static descriptor of some sort (static memory block boundaries, device tree, …).

- Provided by a host or hypervisor.

The node itself doesn’t impose constraints on the location of its primary memory, only the zone may impose such constraints.

The memory manager must then forward it to the primary allocator of the zone that manages it, either by :

- explicit request when the zones don’t have position constraints

- by address calculation otherwise

Anyway, the zone primary memory allocator only ends up with blocks of memory that concern it.

Page cache#

Pages are the base granule for address space mapping. When a process requires any type of memory (stack, heap, file mapping, memory mapping), it calls the kernel so that the latter can allocate it the required number of pages and then configure the virtual address space to map a contiguous block of virtual memory to these allocated pages.

Note : pages being an important resource, the OS may adopt different strategies to reduce unnecessary page consumption, one of them being deferred allocation : the OS will at first allocate a block in the user’s virtual address space but map it to nothing. Later, when the user accesses this unmapped memory, it causes a translation fault. At this moment, the OS will allocate pages for this accessed location and effectively do the mapping. This allows the OS to allocate pages only if they are used. To illustrate how useful this is, we take the example of a user requiring 256 MiB of memory and not accessing it afterwards. With such a system in place, we have simply prevented any wasteful page allocations and saved ourselves 256MiB of memory.

If a page is used by a core, because of how the core’s cache system exploits temporal and spatial memory locality, it is likely that it already has some content of this page in cache. Once this page is freed for any reason, subsequent allocations in this core have a significant advantage in reusing this page. Otherwise, the cache system’s replacement policy will move in new cache lines and discard unused ones, but, there is a possibility this might not immediately concern the recently freed page. Reciprocally, a different core would have little interest to use this page given the choice, as it would cause the related cache lines to be shared among caches of those cores.

As a consequence, it may be interesting for the memory manager to implement a per-core page cache sorting pages by recency to exploit this temporal locality to its fullest : a core requiring a page now looks into its page cache and if empty, allocates a page using its node’s allocator. When the core frees a page, it puts it in its cache for future reuse, and eventually frees the oldest page in cache if the cache is full.

Primary memory allocator : the buddy allocator#

Now that we have described in detail the objectives of the primary memory allocator, let us give a more practical example with a description of one of its possible and most widely known implementations : the buddy allocator.

To solve the primary memory allocation / free problem efficiently, we will first add two constraints :

- the allocator must only support allocation and free of page blocks containing a number of pages that are a power of two. This is the core characteristic of the buddy allocator algorithm.

- the size of the block must be provided at both allocation

(void *alloc(size_t size))and free(void free(void *ptr, size_t size)). This will avoid the need to store block sizes alongside the block as metadata.

A solution to this problem with these constraints is provided by the well known Buddy Allocator algorithm.

This implementation is the one used by linux, among others.

As the Buddy Allocator has already been very well described in many other articles, as such, I will only briefly describe its working principles and provide adequate references as to where to find more detailed explanations.

The main working principles behind this algorithm is to :

- define valid blocks as blocks of size \(2^i\) page, aligned with their own size.

- observe that given a block with two neighbours of its own size, there is only one other block that it can be merged with to form a valid block of the closest greater size. We call this block its ‘buddy’.

- reference valid free blocks by order \(log2(size)\) in a cache, i.e. a linked list array : the list at index i references valid free blocks of size \(2^{(i + page order)}\). Free blocks are used to contain their own metadata, including the linked list node that references them.

- When a new primary memory block is received, divide it into a set of valid free blocks, as big as possible, and reference these blocks in the cache.

If a the allocation of a block of size \(2^i\) pages is required :

- If a valid free block of this size is available, use it.

- Otherwise, if a valid free block of size \(2^j\), (j > i) is available, split it into a set of smaller valid free blocks, of which a valid free block of the required size, use this block and reference other sub-blocks in the cache.

- Otherwise, the allocation fails.

If the free of a valid block of size \(2^i\) is required :

- If its buddy is free, merge them and reiterate with the resulting valid block.

- insert the resulting block in the cache.

The status (allocated / free) of a block’s neighbours can be obtained easily with no dynamic metadata by using a bitmap containing for each valid block, the status of the block (free, allocated). The size of this bitmap depends only on the number of pages \(N\) of the primary memory block \(N\) pages, \(N/2\) valid couples, \(N/4\) valid quadruples, etc…), and its allocation is not a problem, as the primary memory block can have its end truncated to contain it without causing an alignment (and so external fragmentation) problem for the remaining area (it would be the case if the bitmap was put on the start of the primary block).

Documentation :

Secondary allocation#

Though the detailed overview of secondary allocation algorithms is reserved for further chapters, it is necessary to mention it here to better understand where it fit’s in the whole memory manager.

Whereas the primary memory allocator is in charge of the allocation of pages and larger blocks, the secondary allocators handle the allocation of small and intermediate blocks. This secondary allocator will use memory provided by the primary memory manager. This secondary allocator is node-centric : each node will have a secondary allocator using the node’s NORMAL zone as a superblock provider.

Memory manager architecture#

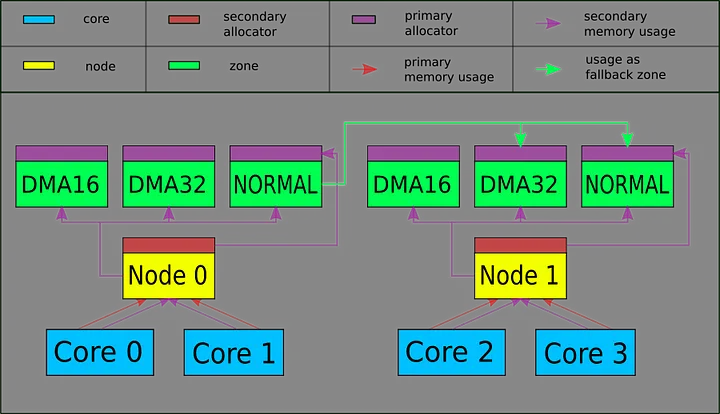

The architecture that we described in this chapter is summarised in the following diagram with an example.

The example consists of a system with 4 cores and two nodes, cores 0 and 1 belonging to node 0, core 2 and 3 belonging to node 1.

Each node has three memory zones, DMA16, DMA32 and NORMAL.

Only the NORMAL zone of the node 0 has fallback zones, namely DMA32 and NORMAL zones from the node 1.

Each zone has its own primary memory allocator.

Each none has its own secondary allocator, using primary memory provided by the node’s NORMAL zone.

Each core uses the primary memory provided by its node, which forwards the allocation request to the required zone.

Conclusion#

After this chapter, we have provided both a high-level view of a memory manager supporting the constraints of the system we defined, and a presentation of one of the most known primary memory allocation algorithms.

The next chapter will focus on the problems and algorithms involved in secondary memory management, thus achieving the overview of the memory manager.