Since this series of articles discuss memory, let’s first define the concept of order of magnitude, which will be used as a more relevant metric than size to differentiate memory blocks.

$$ size = 2^{order} $$

An order increment multiplies the size by 2.

Introduction#

Memory is one of the most important resources of any running program, but is perhaps also one of the least correctly understood by programmers.

In most modern languages, an effort is made to take memory management out of the programmer’s hands.

Even in low level languages such as C or Rust, memory management, though being accessible to the programmer, is confined to the use of malloc/free-ish primitives, implemented in the language’s standard library (ex : glibc).

The underlying memory managers and their implementations are meant to be invisible to the user, which may explain why so many developers are so unfamiliar with the different memory management techniques, and their associated costs, trade-offs, and efficiencies.

This series of article will take the opposite direction, and provide a simplified overview of different memory management techniques, their objectives, trade-offs, and explore how they interact with each other.

In this, we will cover the basics needed to properly understand memory managers, their design and performance.

The theory and designs that I will introduce in this article are based on my study of different kernels (linux being on the list), and on my own implementations and trials.

The memory bottleneck#

As software developers we tend to view memory as an uniform resource, with a constant and negligible access time.

I once asked a group of (computer science) students which type of instructions takes the longest time to complete among :

- memory accesses (read / write).

- computational operations (int / float sum / diff / div).

- control flow operations (conditional (or not) jumps.

They all chose computational operations, which is not surprising given what we are taught at school, and also considering the fact that in a program, memory accesses are simple enough to write (if not just transparent to the programmer) but computational and control flow operations are what most of the code will be about.

However, this is also incorrect in most cases.

Memory is the major bottleneck of modern computer micro architectures, and has been so since CPU cycle time and memory access time diverged, back in the 90s.

Cache#

To mitigate this memory access bottleneck, modern CPU feature a transparent multi-level cache system.

Cache levels store and exchange contiguous memory blocks called cache lines.

Cache lines have a constant size and are aligned on this size.

The cache line is the smallest granule a cache can request memory on, and as a result, is the minumal granule at which all operations are executed from the external memory’s standpoint.

Hence, on a CPU with empty caches :

- a memory read will cause a read of the entire cache line from memory to the cache system.

- a memory write will cause a read plus at some point a write of the entire cache line to the memory system.

- any operation requiring exclusivity on a memory location, like an atomic operation, will require the exclusive ownership of the whole cache line by the CPU’s cache

Additional details :

- Reducing Memory Access Times with Caches | Red Hat Developer

- How L1 and L2 CPU Caches Work, and Why They’re an Essential Part of Modern Chips | ExtremeTech

Page#

Modern systems are equipped with an MMU (Memory Management Unit) that provides, among others uses, memory access protection and virtualization capabilities.

In such systems, two different address spaces are to consider :

- virtual address space : the address space accessed by programs (processes or kernel). Appart from the very early stages of boot nearly all code is using virtual address space.

- physical address space : the address space in which hardware devices are accessible at determined addresses, this includes DRAM, peripherals like UART, USB, ETHERNET, Bus interfaces like PCIE, etc…

The relation between virtual and physical address relies on two concepts :

- the partition of both virtual and physical address spaces in blocks of constant sizes called pages (typical smallest size of 4KiB), aligned on their size. Virtual pages are called pages, physical pages are sometimes referred to as frames.

- the definition by software (using a format defined by the hardware) of a set of translation rules, that associate at most one physical page to each virtual page, called a page-tree or page-table. The MMU uses this informatuon to translate a given virtual address into a physical address.

The minimal granule at which translations can be decided is called the page order \((log2(page size))\) and is a hardware constant.

Though, the operating system may require, for its own reasons, to work on a larger base block.

- Paging and Segmentation | Enterprise Storage Forum

- The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) | Arm Developer

Access Time#

To estimate the time of a memory access, it is necessary to estimate the access time for all cache levels. And to estimate the average access time in a program, it is necessary to know the size of all cache levels and have some notions of each of the cache’s replacement policies, to be able to guess at which level the access might hit.

As such, this estimation is highly unreliable, a better estimation can be made by profiling the execution of the code or by using tools like cachegrind that simulate a cache hierarchy. Though still not exact, these can help the developer in making its software design choice and help evaluate the chosen development paradigms.

To illustrate how wide the differences in memory access times are between cache levels, let me provide indicative values for their access time in CPU cycles and typical size. These numbers are not meant to be taken literally, but rather, serve to show orders of magnitude.

L1 cache : ~ 64KiB, ~ 4 cycles.

L2 cache : ~ 512KiB, ~ 20 cycles.

L3 cache : ~ 4MiB, ~ 100 cycles.

RAM : ~ 8GiB, ~ 200 cycles.

The following thread provides a more detailed comparison to a real CPU benchmark :

With this in mind, in order to make a program as efficient as possible, the two fundamental rules will be :

- To reduce as much as possible the amount of memory accesses.

- If possible, increase spatial and temporal locality, i.e. to generate accesses at memory locations close to previous ones and not long after their use.

System constraints : NUMA#

NUMA (Non Uniform Memory Access) is a qualifier for a system where the physical memory access latency for a same address depends on the core the access originates from.

For example, in such systems, there may be multiple primary memory banks, located at different places in the motherboard, and multiple cores, also located at different places.

To simplify the management of these systems, we can conceptually group memory banks and cores in sets that we will call node (linuxian terminology), the node of a core and the node of a memory bank being the only factors taken into account when considering the latency of the core/bank access.

In all this series, we will place ourselves (and our allocators) in a NUMA system.

ie: a system with :

- One or more cores, i.e. processing elements, cpus…

- One or more blocks of primary memory, i.e. primary memory that is provided as-it in the system (eg : DRAM), mapped in kernel address space and accessible by all cores of the system, but with a latency that may depend on the core (see node below).

- One or more nodes.

In this system, the first objectives of our memory manager is to :

- Reference primary memory blocks of each node.

- Provide a primary memory allocation / free interface to each core.

- Ensure that memory allocated to a CPU is as close as possible to this CPU.

Additional details on NUMA :

- What is NUMA ? | The Linux Kernel documentation

- Non-uniform memory access | Wikipedia

- Understanding NUMA Architecture | LinuxHint

Fundamental orders#

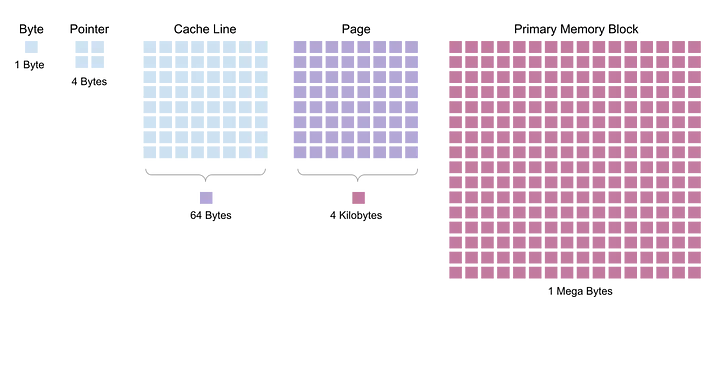

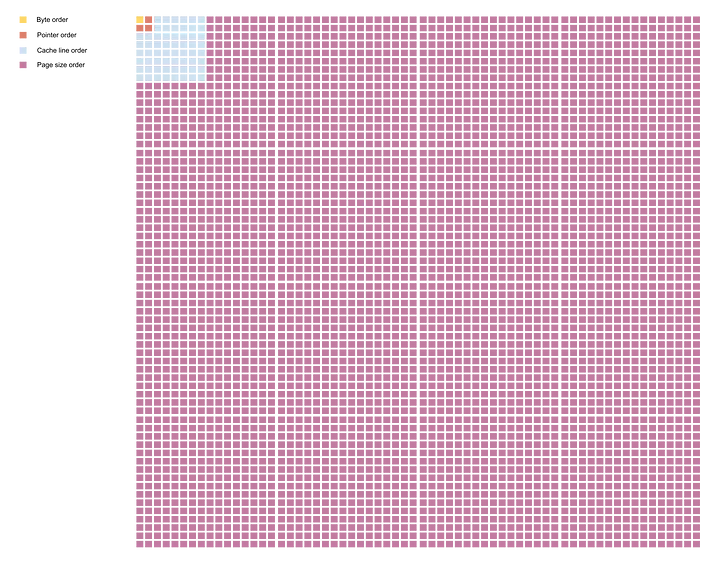

Here are some orders to keep in mind when discussing memory management :

- Byte : order 0, constant.

- Pointer : order ~ 2 or 3 (= 4B or 8B), depends on the size of the virtual address space.

- Cache line : order ~ 8 (= 64B), depends on the cache management system.

- Page : order ~ 12 (= 4KiB), depends on the granularity of the page-table.

- Primary memory block : order ~20 to 30 or more (1MiB -> 1GiB or more).

Allocation types#

With those orders in mind, let’s consider the different allocation types, to help us classify allocators and the objectives :

- small blocks (< cache_line_size) : frequent allocation, used for a huge part of object allocations (average size of malloced structures = 60 bytes), must be fast, small blocks must respect the fundamental alignment.

- intermediate blocks ( < page_size) : least frequent allocation, used for larger structs, may not be fast. Intermediate blocks must respect the fundamental alignment.

- page ( = page_size) : used by the kernel to populate page-tables, usage by secondary allocators as superblocks, must be very fast. Pages must be aligned on the page order.

- page blocks : contiguous page blocks, used by secondary allocators, less frequent. Page blocks must be aligned on the page order.

Physical memory management, 🐔 & 🥚 problem#

Physical memory management is a difficult problem, because it cannot require the use of any other allocator, as it is THE first allocator, the one managing physical memory, which is provided as-it.

It cannot use per-page or per-page block metadata inside those pages (or page blocks, blocks), but it split the block of physical memory that it manages into two :

- allocatable pages.

- metadata for the allocatable pages.

Let’s note two things first :

- Allocating a page is a subproblem of allocating a page block.

- An allocator able to provide page blocks can be used as a memory source for memory allocators that allocate smaller blocks.

Hence, we can define two types of memory allocators :

- Primary allocators who manage primary memory blocks, and that allocate page blocks in those.

- Secondary allocators who divide page blocks provided by primary allocators into smaller blocks that they allocate to their users.

The anatomy of a primary allocator, (the buddy), and of several secondary allocators will be detailed in the next chapter.

Crossing accesses#

I stated before that the base granule for memory operations is the cache line.

Now, let’s look the following C code, assume that compiler optimisations and registers do not exist, and try to predict what accesses will be generated by the assembly produced by the compiler :

int main() {

/* Part 1. */

uint8_t i = 5;

uint64_t j = 5;

/* Part 2. */

uint8_t t[16] __attribute__((aligned(8)));

*(uint64_t *) (t + 1) = 5;

}

In part 1, the compiler will generate two memory writes instructions targetting the stack (no registers) for i and j : i will be stored using a 1-byte write, and j will be stored with an 8-bytes write.

In part 2, we define char array of 16 bytes on the stack, whose first element’s address is aligned on 8 bytes (__attribute__(…)). Let its address (dynamically determined in a real world example since the stack is used to store local variables) be 56 for our exmple. To perform the write, the compiler to generate a 8-bytes write at addresses [57, 64].

For the record, it is explicitly mentioned in all the C language standards that this type of pointer casts has an undefined behavior.

Now if we suppose that the cache line size of our system is 64 Bytes, we just generated a memory write that spans across two cache lines : the first part from 57 to 63 (on cache line ranging from addresses 0–63), the second on 64 (on cache line ranging from addresses 64–127), this type of access being infamously known as an unaligned access.

Unaligned accesses may carry a severe penalty and are generally something to avoid generating, as it may lead to undefined behaviors. The example we described was fairly simple, and the answer “ yeah I don’t care generate two accesses instead of one ”, could fly. But supporting this in HW may make CPU designers unhappy.

But if an access can cross cache lines, it can also cross a page boundary and can involve pages of virtual memory, which could be mapped with different access privileges and cacheability (another attribute held by the page table).

What should the CPU do in this case ? Fault ? Generate two accesses on the different cache lines with different attributes ? CPU designers just went from ‘unhappy’ to ‘complaining’.

Worse case : one of the two virtual page could be mapped, and the other could be non-mapped.

What should the CPU do in this case ? Perform none of the accesses ? Perform the valid part of the access, and not the other ? CPU designers just transitioned to ‘angry’.

Worse, the access could be an atomic instruction that requires the exclusivity on one cache line, which is a hell of a heavy work for a CPU.

What should the CPU do in this case ? Fault ? Require the exclusivity on two cache lines and split the access ? CPU designers just transitioned to ’trying to find out where you live’.

Some architectures like the old ARM processors (ARMV4T) did not support unaligned accesses, others tolerated it and optionally trapped them, or profiled them so they could be reported to the respectful developer.

The safest certainty we have is that they should be avoided if at all possible. As a matter of fact, the C compiler never generates any unaligned memory access.

Except when it does.

I once had an unpleasant experience dealing with a version of the C standard library that had some functions that generated such accesses. For the record, those functions were memcpy and memset, and they generated unaligned accesses by uncarefully extending the read / copy / write granularity without checking the alignment of source/dest addresses.

Additional reading :

- Unaligned accesses in C/C++: what, why and solutions to do it properly | Quarkslab’s blog

- Unaligned Memory Accesses | Linux Kernel Documentation

Impact on the memory manager#

The key takeaway to be remembered from the last paragraph is that unaligned access cause perf and power hits and therefore should be avoided.

This means that any object legitimately instantiated in memory should not generate unaligned accesses.

For example, an instance of the following struct allocated with our memory allocator

struct s {

uint32_t x;

uint8_t y;

uint32_t z;

};

should not generate any unaligned accesses when accessing any of its fields.

The C compiler (unless manually instructed to do so by the snarky developper) will add padding to this struct the following way :

struct s {

uint32_t x;

uint8_t y;

uint8_t pad[3];

uint32_t z;

};

But for every field to be accessed without unaligned accesses, when providing a memory block B, an allocator must ensure that B’s start address meets alignment requirements for any primitive type that can be placed in an aligned manner in B.

Eg " in 64 bits systems, a block of size 1 can be placed everywhere in memory, a block of size 2 start at an address that is a multiple of 2, a block of size 4 must start at an address that is a multiple of 4, a block of size 8 or more must start at an address that is a multiple of 8._

If you wonder, the documentation of the malloc C function, states a similar constraint :

“If allocation succeeds, returns a pointer that is suitably aligned for any object type with fundamental alignment.”

Impact of fundamental orders on the allocator#

The different orders we defined to characterise our memory system may vary among different systems, their variations having an impact on the memory manager and the amount of allocated memory for a same program:

Byte order : 1, invariant.

Pointer order : has a direct impact on the amount of memory used by a program.

Indeed, when reading the source of large C projects, linux being a good example, it is easy to notice that most data structures are packed with pointers. A variation of the pointer size will cause a similar variation on the size of those structs.

Cache line order : has an impact on the secondary memory manager.

Indeed, the cache line is the base granule on which synchronization instructions operate on modern CPUs : when you execute an atomic operation, the core’s memory system requires the exclusivity on the cache line, then executes your operation, then confirms that the exclusivity was held during the whole operation.

For this reason, it is important that memory allocated to an end-user that may use synchronization instructions on it, is allocated on the granule of a cache line (and aligned on the cache line size). This is needed to avoid a situation where two users could, for example, attempt to lock two different spinlocks, present in two different structures each one of size cache_line_size / 2, but allocated on the same cache line by the memory manager. In this case, when trying to acquire the spinlock and requiring the exclusivity of the cache line. Each of the two users will be blocking the other’s ability to acquire the other spinlock, thus creating additional, unnecessary and expensive memory access conflicts.

Page size order : has a possible impact on internal fragmentation of secondary allocators, and on efficiency of secondary allocators.

Secondary allocators, as stated before, manage superblocks provided by primary allocators, and use those to allocate smaller blocks. Increasing the page order will increase the minimal superblock size, and so, the amount of primary memory allocated at each superblock allocation.

Now let’s say that a secondary allocator is constructed and receives a single allocation request for 64 Bytes of memory. A superblock will have to be allocated, and will be used to provide the 64 Bytes.

Now if no more memory is required from this secondary allocator, the whole superblock will still be allocated and not usable by other software. This could cause a large external fragmentation.

Now, increasing the superblock size will also decrease the rate at which superblocks will be allocated, which will slightly increase the allocator’s efficiency.

Conclusion#

This chapter will have stated what I believe are the most basic things to keep in mind when speaking of memory managers.

In the next chapter, we will be focusing on the structure of the primary and secondary memory managers.